OUT OF THE EXCLUSION ZONE

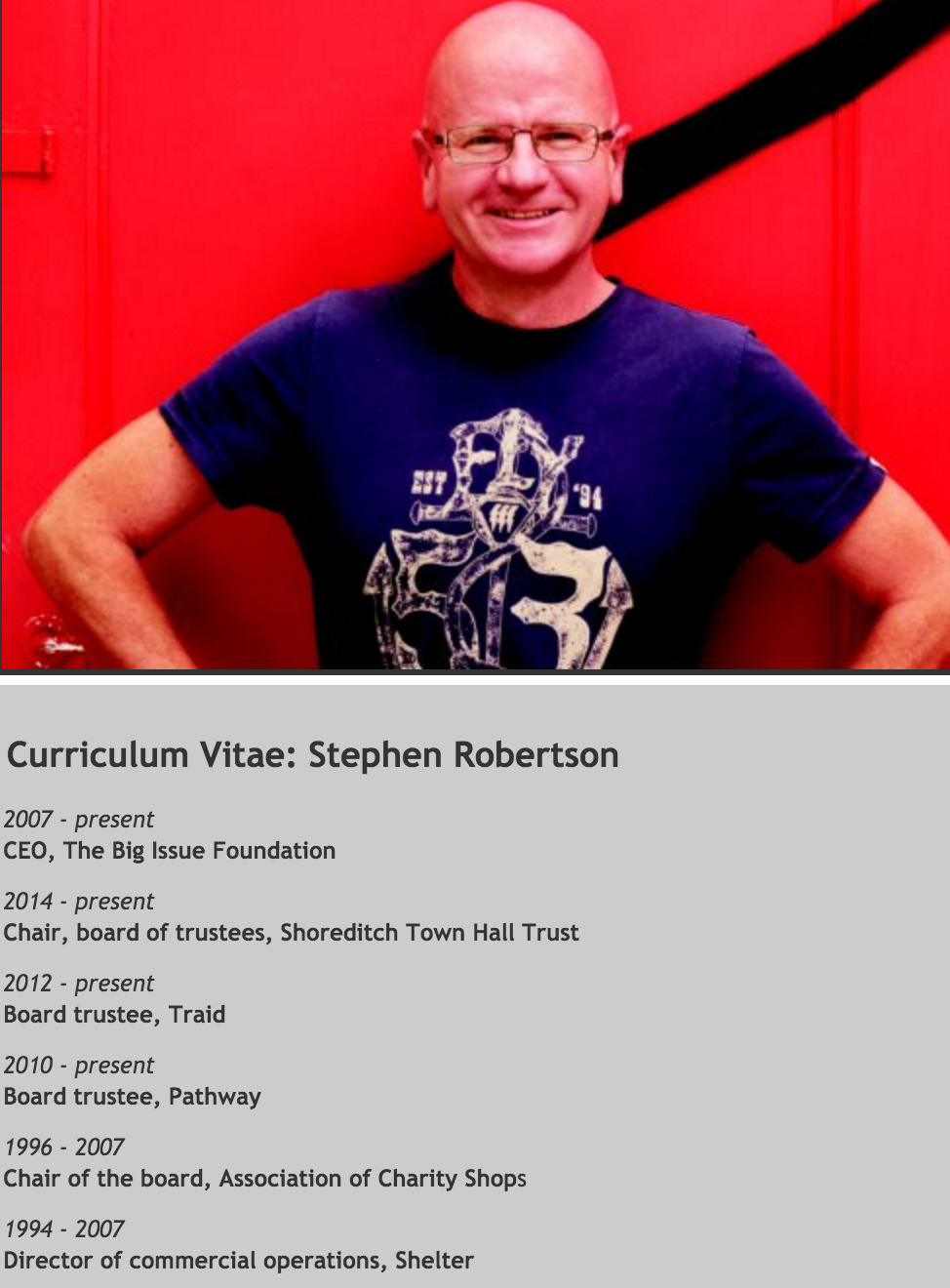

As Communicate magazine announces Stephen Robertson as one of the keynote speakers at this year’s Employer Brand Management conference, Andrew Thomas catches up with the CEO of the Big Issue Foundation

Photographs by Jeff Leyshon

"The challenge for an established brand like ours is to create moments of engagement.”

"The challenge for an established brand like ours is to create moments of engagement.”

It’s a statement that you’ll hear from CEOs, CMOs and communications directors across the spectrum of retail marketing. But when it comes from Stephen Robertson, the chief executive of the Big Issue Foundation it has a resonance that goes beyond marketing speak. “We are a well-known brand and because of that a Big Issue vendor can become part of the street furniture. ‘There’s a bus stop, there’s a post box, there’s a Big Issue vendor.’ It means our vendors and our brand can become invisible,” he says.

The Big Issue Foundation will be 20 years old this autumn (it celebrates with a fundraising party on 22 October). It was created four years after the launch of the Big Issue magazine, a social business originally designed to create a legitimate earning opportunity for the homeless and the socially and financially excluded. Robertson joined eight years ago bringing with him experience and understanding in the three skills of charity, retail and communications. Where the Big Issue exists to provide direct, and often life-saving, income for homeless people through the street sales of the magazine, the Big Issue Foundation exists to address the underlying causes of homelessness, providing a lifeline for many. Robertson started in 2007, following a 13-year stint at Shelter.

For many, a career in the charitable space is as much a vocation as teaching, medicine and journalism. But for the young Robertson, brought up in the genteel seaside resort of Bournemouth, his arrival in the third sector happened more because of his passion for pop music. After leaving university, Robertson, an obsessive music fan, sought out a job at Our Price, a record shop chain from a time when records were bought in large numbers. He quickly rose through the ranks, taking charge of the London, Essex and East Anglia region. Without intending to do so, 10 years at Our Price had made him a credible expert as a retailer. It wasn’t enough, though. Robertson felt there was something missing, but equally felt that outside the narrow constraints of the music industry, his experience didn’t count for much. He applied for a few jobs, but nothing materialised. A chance read of a newspaper while waiting for the local Indian takeaway to prepare his order brought to his attention a role running the southern retail operations of the Marie Curie Cancer Care charity. He applied and got the job.

“It really was chance and happenstance,” says Robertson, modestly. “Charities were diversifying their income strategy to become less reliant on legacy funding. It was also a time when charities were beginning to understand the benefits of specialist skills. They were beginning to hire experienced marketers to help them market and, in my case, specialist retailers to help with the retail operation.”

Although he remained a retailer, his migration to the charity sector was a move from which he would never return. “The thing that really engaged me from the outset was that running a charity required business skills, but the outcome is good work in the broad social sense,” he says. “I was able to transfer my skills from the profit to the not-for-profit sector and actually help change and save lives.”

As an employer in the charity space Robertson acknowledges the impact that has on many people, “It is incredibly motivating to make a difference. Everyone in retail works incredibly hard, so the idea that knowing that what you are doing has a greater meaning is such a powerful force.”

Robertson was at Marie Curie Cancer Care for a year before moving to a similar role at Shelter. This was a national role and started at a time when homelessness had been aggressively rising during the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was a high profile role. If there is an order of status in the charity sector, Robertson was definitely working for the equivalent of a blue chip firm. He was there for 13 years and had just started to think about what next to do with his career when he was approached by the Big Issue Foundation. “It was perfect timing,” he says. “I wanted to get closer to the work that charities fund. To continue funding, but also get some experience on the front line. Contrary to popular perception, the Big Issue Foundation isn’t that big. It gets noticed because of the visibility of the vendors, yet within the business the number of people who produce and take the magazine to market is less than 75 people and the charity that takes the business journey forward, the part where I am most involved, is less than 35 people.” Last year, the Big Issue Foundation helped over 6,000 people, including 2,000 vendors, with a headcount of only 100 people. As Robertson adds, “You don’t really get any more front line than that.”

The Big Issue was launched in 1991 by John Bird and Gordon Roddick (co-founder, with his wife, Anita, of the Body Shop). The idea came after Roddick bought a copy of a magazine called Street News from a homeless man in New York. Old drinking buddies, the two decided to create something similar in London. Roddick had the funds to make it happen; Bird, a printer and small-time magazine publisher, the experience. Their initial idea was for a social enterprise that would enable homeless Londoners to develop independence by selling copies of a magazine written by professional and well-known journalists. From London it spread nationally, and then globally. As Robertson says, “The Big Issue helps people who are or have faced social or financial inclusion normally manifesting itself in periods of homelessness. It creates an opportunity for them to legitimately start their own business by buying and selling the Big Issue with their own cash. When a homeless person becomes economically active in the market place there then arises further issues that contributed to, or have arisen because of, the issues and experiences they have had. The foundation was set up to deal with those issues.”

A vendor is often lent the money to buy his first few copies of the Big Issue. After that, the foundation will help the vendor with housing, accommodation, financial inclusion and health issues under an aspirational agenda. “Through that retail process we help put people back into the mainstream,” adds Robertson.

The two divisions operate as separate legal entities, with John Bird staying in the limelight as founder, publisher and public figure behind the Big Issue and with Robertson as the CEO of the Big Issue Foundation. Bird also sits on the board of trustees.

Regardless of its intentions, the Big Issue and the Big Issue Foundation have not escaped media criticism. Considering that its brand ambassadors, the vendors, are also society’s most disadvantaged, it is perhaps surprising that it doesn’t make front page news more often.

Regardless of its intentions, the Big Issue and the Big Issue Foundation have not escaped media criticism. Considering that its brand ambassadors, the vendors, are also society’s most disadvantaged, it is perhaps surprising that it doesn’t make front page news more often.

“I have a little badge on my computer screen that says, ‘Hated by the Daily Mail,’” Robertson says. “Ultimately we are the last chance resort for many people. They will have fallen through many other safety nets before they hit the concrete floor of the high street where we operate, and consequently we will encounter many occasions where our name is dragged through mud. We have a code of conduct, and there are stages where we will eventually take away a vendor’s badge. The public aren’t backwards in coming forward to tell us the things vendors are doing wrong. We work with the police and other bodies to do the best we can but, by definition, we are represented by a workforce we don’t employ and this can create situations that can be difficult to manage. Often the situations are a magnifying glass for people’s prejudices. It can create headlines.”

While those situations can make media relations a game of constant crisis management it can also work in the Big Issue’s favour. “What we constantly try and do is get people to look behind the badge. One of the communication challenges is that term – homeless. Antisocial behaviour is not homelessness. Homelessness is an output of something else. An output of social and financial exclusion. Many people are only three pay cheques away from being homeless themselves. That’s compounded when you have no family to support you, no savings, no friends and there is no one that you can turn to,” Robertson says.

Many are still to grasp the transactional process of the Big Issue; that the vendors are running their own micro-business having bought the magazine from the publishers. Robertson is definitely against the concept of begging, or of people just giving vendors money without seeing the magazine. As well as undermining the impact of the advertising, sold on the basis of the magazine’s circulation, he feels it undermines the process of change. Robertson and the Big Issue Foundation prioritises this message, and have run some interesting campaigns of corporate engagement. It started when HSBC sales staff volunteered their time to train Big Issue vendors. As part of the process the HSBC staff donned the Big Issue tabard, selling magazines themselves. The feedback session showed that the HSBC staff learned as much as the Big Issue vendors, on self-awareness, humility and how stereotypes affected people’s judgement. The net result was that it changed the way HSBC trained its staff.

The Big Issue has gone on to replicate or modify that process with other financial and professional services firms, with corporate law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer making graduate trainees spend time working with a Big Issue vendor as part of the induction process. While Freshfields’ graduate recruitment partner, Simon Johnson, acknowledges that it does form part of the firm’s CSR programme, he is quick to point out other benefits to the tie-in. “It’s a useful confidence-building exercise for the trainees,” he says. “Being put in someone else’s shoes really brings them out of their comfort zone.”

As well as the benefits to companies, Robertson is keen to point out the uniqueness of these corporate tie-ins. As he says, “It isn’t critical of any other organisation to say this, but you really can’t do anything like this with other charities. You can’t be a Marie Curie cancer nurse for the day.”

The rate of homelessness has increased considerably over the past five years. Recently-released government statistics show that 2,714 slept rough on any one night in 2014, a 55% rise on 2010 figures. Yet it wasn’t that long ago that homelessness was on the decline. As recently as 2008, all London mayoral candidates had pledged to end homelessness, with the winning candidate, Boris Johnson, pledging to end rough sleeping by 2012. Could there be a possibility that if the Big Issue Foundation was too successful it could bring about its own demise? Like most people in the third sector, Robertson is reluctant to get drawn into criticising public policy, “We can talk about austerity, hospital closures and so on, but ultimately this is about social and financial exclusion and I think that it is highly unlikely we will see a time when there aren’t some who fall out of the bottom end. Wherever that bottom end is there will be those that will need our help.”