SOME ARE BORN GREAT

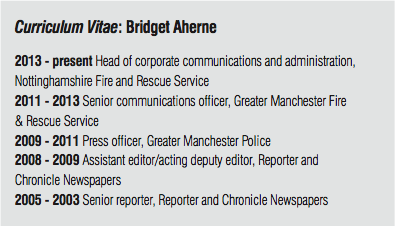

As this year’s Chartered Institute of Public Relations’ ‘PR Director of the Year’ award is thrust at Bridget Aherne, Andrew Thomas finds out how she is achieving greatness in blue light comms

Photographs by Sam Friedrich

There are some jobs almost ubiquitously paired with the term ‘vocational.’ Medical careers are one, religious ministry another. Journalism is the same. Yet for aspiring journalists, it’s not just the pursuance of a career; for many the need to write is almost dermatological, a skin condition that needs to be scratched. For Bridget Aherne, Nottinghamshire Fire & Rescue Service’s head of corporate communications and administration, the drive to write lay dormant until she started university. Yet that desire to tell stories had always been there and, once discovered, has determined most of her work-related decisions.

There are some jobs almost ubiquitously paired with the term ‘vocational.’ Medical careers are one, religious ministry another. Journalism is the same. Yet for aspiring journalists, it’s not just the pursuance of a career; for many the need to write is almost dermatological, a skin condition that needs to be scratched. For Bridget Aherne, Nottinghamshire Fire & Rescue Service’s head of corporate communications and administration, the drive to write lay dormant until she started university. Yet that desire to tell stories had always been there and, once discovered, has determined most of her work-related decisions.

By a wide margin, Aherne was the youngest of three. Her sisters were almost old enough to be her parents and, in turn, her parents were old enough to be her grandparents. Her father was a first generation immigrant from Ireland, her mother second-generation. “I was brought up in Manchester, but we were very much part of this whole Irish diaspora experience. I was completely immersed in the culture,” says Aherne. “As I’ve got older I’ve realised how much this contributed to my career. Socialisation, communication, music, dancing; all these areas just added to my abilities as an effective storyteller.”

As the youngest, Aherne was undeniably spoiled, but her upbringing was far from prosperous. During her interview with the CIPR and the IoD for the ‘PR Director of the Year’ honour, she talked about her working class childhood. “I was a poor kid from a really poor area of Manchester. My parents had to work really hard to put a roof over our head and food on the table. I think it’s positive that in this profession, with hard work and the right approach, anyone can go anywhere,” says Aherne.

Although she feels guilty in acknowledging the limitations of her school, Aherne doesn’t remember being given much direction or guidance. There was certainly no school magazine. “Although there was a little bit of pushing towards certain directions, when I look back I think there was a sense that, for people from my background, there wasn’t really an opportunity to aspire to a career in journalism.”

Outside of school, she had been a keen and gifted Irish dancer. Unsure of what route to take, but thinking performance might be one direction to follow, she managed to get a place at Huddersfield University to study a theatre and media studies degree.

Surprisingly, she didn’t like the theatre studies side of her course. She didn’t mind the storytelling element but performance left her cold. Then, in her first semester, she opted for a journalism module within the media studies component. “It sounds really cheesy, but it was a light bulb moment for me,” says Aherne. “I decided, in that first class, ‘This is it.’ I can apply my passion for storytelling, for communicating, for socialising. I realised I loved getting immersed into a subject, finding out the different angles of an issue and then translating it into a story.”

From that moment, all the modules Aherne took were relevant to the end goal of journalism. Her extracurricular choices were made with the same intent – for one, she helped launch the campus radio station.

From that moment, all the modules Aherne took were relevant to the end goal of journalism. Her extracurricular choices were made with the same intent – for one, she helped launch the campus radio station.

Yet, on finishing her degree it looked like it might have all been in vain. “I wrote to every editor on every newspaper in greater Manchester. I got a couple of letters saying ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’ But, in hindsight, it was very much the kind of response you’d expect for someone with a theatre and media studies degree.”

For Aherne, however, what followed was fortune. She took a customer services job at the local AA call centre. Fate came calling – the floor below the call centre housed the AA travel news operation. “An opportunity came up. I had the student radio station experience and had studied radio journalism on my course and I persuaded them to take me on. It was great. I did a lot of the information gathering, and then supplied it to the stations that took a voice service.” More importantly it gave her the inspiration to apply for, and the credibility to be accepted on, the NCTJ (National Council for the Training of Journalists) conversion course.

She finished her training in 2005. It had been three years since leaving university. Even now she can still vividly picture her first day at the Reporter and Chronicle Newspapers. “I can’t remember the actual duties, but I do remember certain elements of the day. What I wore, leaving the house, getting a text message from my boyfriend at the time saying, ‘Good luck on your first day as a journalist.’ I couldn’t believe it. I had worked so hard to get there.”

From reporter to senior reporter to assistant editor, promotion came quickly. But in 2008, every local news journalist’s career was uncertain. The banking crisis brought with it a property downturn and for local newspapers, this was disastrous. The industry had already seen the internet decimate readership and classified advertising and the largest display advertising sector, property, was now going the same way. Says Aherne, “I suddenly felt my opportunities contract. We weren’t expanding online at the rate that other newspapers were. The investments had been planned, but the recession hit before they’d been made.”

Aherne was concerned but not panicking. She certainly wasn’t actively seeking a new job, let alone thinking of leaving jourmalism. “I had always envisaged myself staying in journalism, but when I saw the opportunity at Greater Manchester Police (GMP), having seen the PR developments they had made and really noticed a change in their approach and their social media and media relations activity, I thought ‘Yes, that’s it. That’s for me.’”

Unlike many journalists, Aherne had never seen PR as the dark side. “I had actually admired what many of those in PR and comms had done for me as a reporter,” she recalls. “I had seen bad, but I had seen some very good, particularly from the likes of council press offices, police press offices, fire service comms. Those kind of groups. I had respect but, yes, I did go into it thinking I could return to journalism. It was only a six month contract to begin with, so it felt like I was sticking my toe in the water. But the minute I started, I thought ‘Yes, this is it.’ This is really professional communications. This is really contributing to the safety of greater Manchester. I instantly felt I was doing something important.”

Aherne acknowledges that, in hindsight, what she wanted was diversification. “Suddenly my role was much more varied. The engagement with the community and with the all the various stakeholders was suddenly so much more important. Once I got there, I never considered going back to journalism, and I haven’t since.” She joined the GMP as a press officer, reporting into Amanda Coleman, the legendary head of communications already revolutionising police communications. “It did feel like a revolution,” says Aherne. “We were one of the first police organisations to use Facebook, the first to use Twitter, ensuring every beat communicated directly, each with its own account.”

Aherne acknowledges that, in hindsight, what she wanted was diversification. “Suddenly my role was much more varied. The engagement with the community and with the all the various stakeholders was suddenly so much more important. Once I got there, I never considered going back to journalism, and I haven’t since.” She joined the GMP as a press officer, reporting into Amanda Coleman, the legendary head of communications already revolutionising police communications. “It did feel like a revolution,” says Aherne. “We were one of the first police organisations to use Facebook, the first to use Twitter, ensuring every beat communicated directly, each with its own account.”

It was a frontier time for many organisations writing the rules of social media aligned communications. Most organisations, public or private sector, were in the process of understanding the new tools, and many would think that the police would be rooted in the most traditional methods of communicating and engaging with their publics. Not so, according to Aherne, “What was brilliant was that there was an encouragement to go beyond the policy. The policy was a framework and you had to make sure that you stuck to the spirit of it but not, necessarily, to the letter of it. And under Amanda Coleman we were encouraged to try things.”

Aherne says this was an invaluable lesson, “That job set me up for my career. I now look for managers who allow that approach in me as a manager. The ethos I try to create around my team is for them to research what they’re going to do and then try new things. It’s important to have a healthy appetite for risk. It certainly felt like that at the time and it created that ongoing enthusiasm that has stayed with me.”

After Aherne had been at the GMP for nearly two years, the police force carried out one of the most lauded and reported social media communication campaigns. This was autumn 2010 and a new government had a mandate to introduce national austerity and was determined to impose cuts on the public sector. The GMP wanted to ensure the public understood the depth of modern policing, perhaps as a pre-emptive strike against cuts too swingeing. On 14 October, the Greater Manchester Police live-tweeted every report and every incident for a 24-hour period. “Policing is so much more than banging down doors and locking up people. Most of the time it’s about the public looking for solutions to issues that aren’t police related at all. Being part of that day felt very special. We were only intending to do a bit of social media activity to highlight the work we did, but we knew we were doing something different when we were getting press calls in from news outlets in Australia, Toronto and elsewhere. Becoming part of this worldwide story that day felt pretty special.”

After nearly three years though, Aherne felt it was time for a move. Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service were advertising for a senior communications officer. “I was fortunate at GMP because I was able to specialise in response communications. It’s permanent crisis comms – something happens, you hadn’t planned for it, you’ve got to deal with it. It’s stuff that matters. But there is no room for the specialist any more. You can’t be single discipline. The job of the fire services is much more about prevention and that gave me an opportunity to hone my proactive public relations skills. When I saw the fire job I thought, ‘Bingo – that’s for me.’”

It was at the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service that Aherne took on the responsibility for internal communications. In the private sector, the internal comms professional is becoming increasingly specialist. In the public sector there is less space for such indulgence. “I do see internal communications as a rightful standalone discipline, but in many areas of the public sector now there aren’t the resources to have a dedicated internal comms team. But just because you don’t have a dedicated internal comms team that doesn’t mean that you can be second rate in internal comms. I would say multi-disciplinary communicators have to be razor sharp at everything, they have to be as good, if not better, than single discipline counterparts.”

In autumn 2013, Aherne added another discipline to her skill-set. Moving to Nottingham (a big step for the self-titled ‘terminal Manc’) to join the Nottinghamshire Fire and Rescue Service, she took up her current role of head of corporate communications and administration. It’s an interesting role, incorporating the management of the call centre function. Aherne doesn’t see any discrepancy in the role. “Put simply, face-to-face contact is with firefighters, and everything else, all non-face-to-face contact, comes to my team. Administration is public-sector speak for customer service. So actually it’s a good fit with corporate communications because the same values need to come through.”

Outside of work, Aherne is heavily involved with the CIPR and also with FirePRO, the network of fire communicators, with which she recently took up the vice-chair position. She is reluctant to be drawn into details, but two years ago Aherne witnessed a serious work incident which she feels changed the balance in her life. “I was a bit of a workaholic. Although I’ve got a better balance now, I am more determined, both in my professional life, but also my personal approach now is to grasp at every straw of opportunity that is put in front to me.”

She’s clearly enjoying her time at Nottinghamshire Fire and Rescue Services and although she is wary of being pigeonholed, she does see her future in the public sector. As she told the judging panel for the CIPR award, “There are still lots to improve and build on, but ultimately I like working for organisations that help improve people’s lives.”